On the art of learning a new language

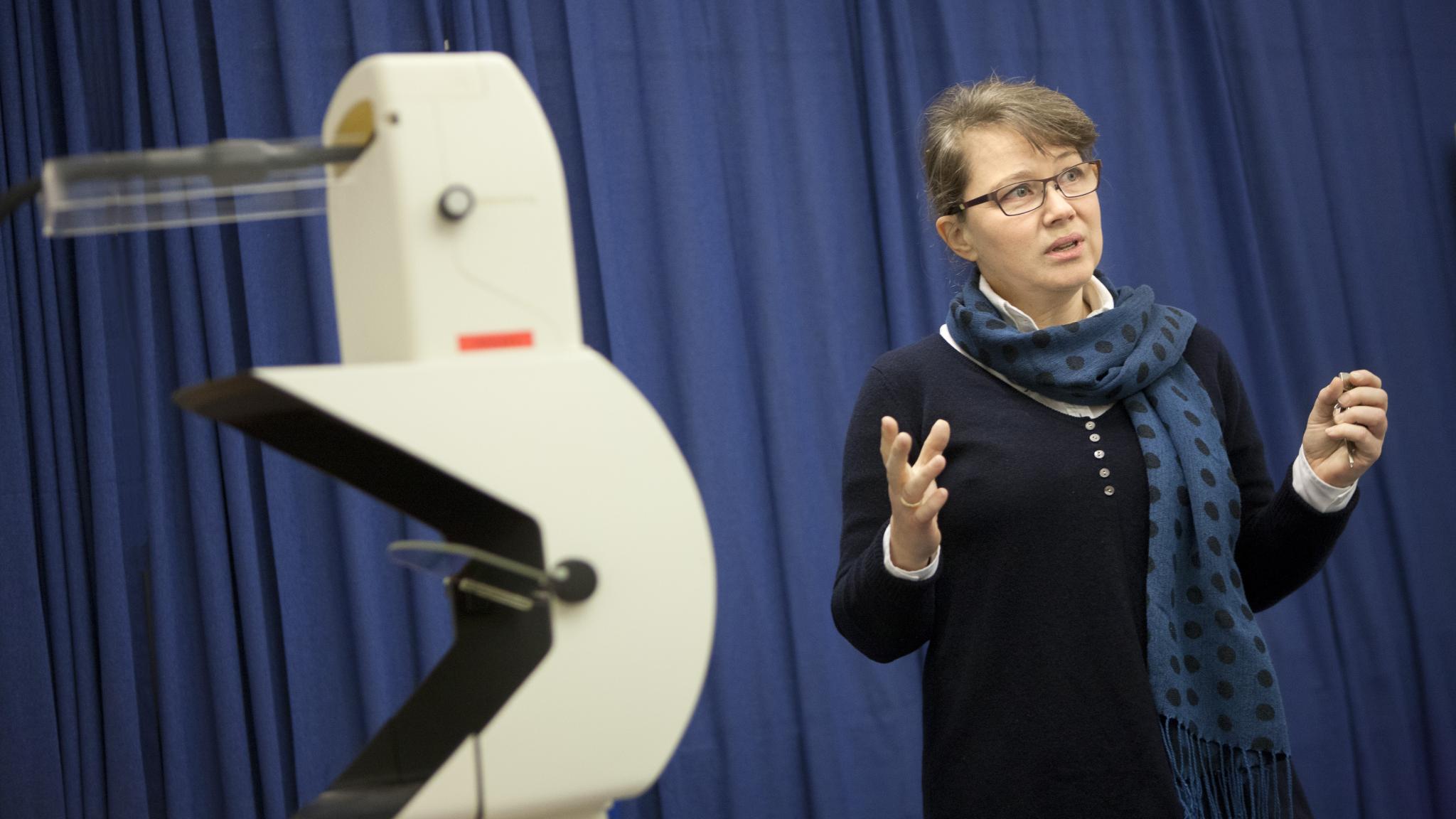

How do we speak and understand languages? And how do we learn a new language? What happens to our gestures? Is our first language affected when we learn a new one? These are some of the questions Marianne Gullberg is trying to answer in her research. At the same time she rejects several myths about language learning.

Marianne Gullberg

Professor of Psycholinguistics

Wallenberg Scholar

Institution:

Lund University

Research field:

Adult second language learning and multilingualism in speech and gesture; language processing, including neurocognitive aspects.

– It’s fun to explode myths. She speaks fast and intensely. Her eyes sparkle and the words flow from her mouth accompanied by some lively gestures. You understand that language research is not just a job – it’s a passion. We’ll return to the gesturing and the myths associated with gestures later.

Marianne Gullberg is Professor of Psycholinguistics at Lund University. Briefly put, psycholinguistics is the study of the relationship between language, thought and brain. Quite simply, what it is that we do when we speak and understand languages. Something that we don’t often think about when we speak our native language.

– It’s an incredibly fast process – a question of milliseconds. During that time we move from a vague idea about what we want to say to choosing the right words, grammar, speech sounds, intonation and gesture. The reverse process, understanding what someone else is saying, is no less fascinating.

Unexplored area

Human language is the most complex communication system we know of. Language is also our tool for thinking. It interacts for example with emotions and memory and is driven by the same neurological apparatus.

– But how do we really learn a language? It is generally not until we learn a new language that we realize how difficult it is. What interests me is precisely how we learn a language when we already have one in place. How do the different languages interact and influence each other? The area is surprisingly unexplored, she says.

Myths and double standards

In Marianne Gullberg’s opinion there are a great many myths surrounding language learning and many decisions of relevance to society are ill informed. She also points out a strange double standard as regards multilingualism.

– We want our children to learn English at an early age because early learning is a good thing. But a child who is multilingual in for example Turkish and Swedish is regarded as a problem. This is a peculiar attitude.

Marianne Gullberg says that all research clearly shows that multilingualism is a good thing. By global comparison it is rather strange to speak only one language.

– Using several languages is like exercise for the brain and gives some protection against dementia. In the world in general multilingualism is the norm rather than the exception. In many parts of Africa pre-school children speak three languages and when they begin school they learn three more.

Gestures with small differences

Professor Gullberg has also studied Swedes learning French and vice versa. She has not only looked at how they talk but also how they gesture and has thus been able to explode another myth.

– It turns out that French and Swedish people in fact gesticulate just as much. Instead they differ in how they gesture. This difference makes it seem to Swedes as if French people talk more with their hands than we do. French people also use facial expressions and their shoulders more often.

– It’s a matter of small, subtle differences. French people are in fact quite restrained but use more rhythmic gestures than we do to emphasize what they are saying.

Her appointment as a Wallenberg Scholar means that she can now penetrate adults' language learning more deeply.

– I can delve deeper into the process from the earliest stages of learning to full-fledged multilingualism.

Technology for the Humanities

One aspect of how languages influence each other is accent. Marianne Gullberg and her research team will be looking at accent more closely in a new project.

– Accent is not just a question of pronunciation. We’re also going to study how gestures are affected since emphasis, intonation and rhythm are also expressed through the hands. Is a person speaking perfect French but gesturing in Swedish perceived as having an accent?

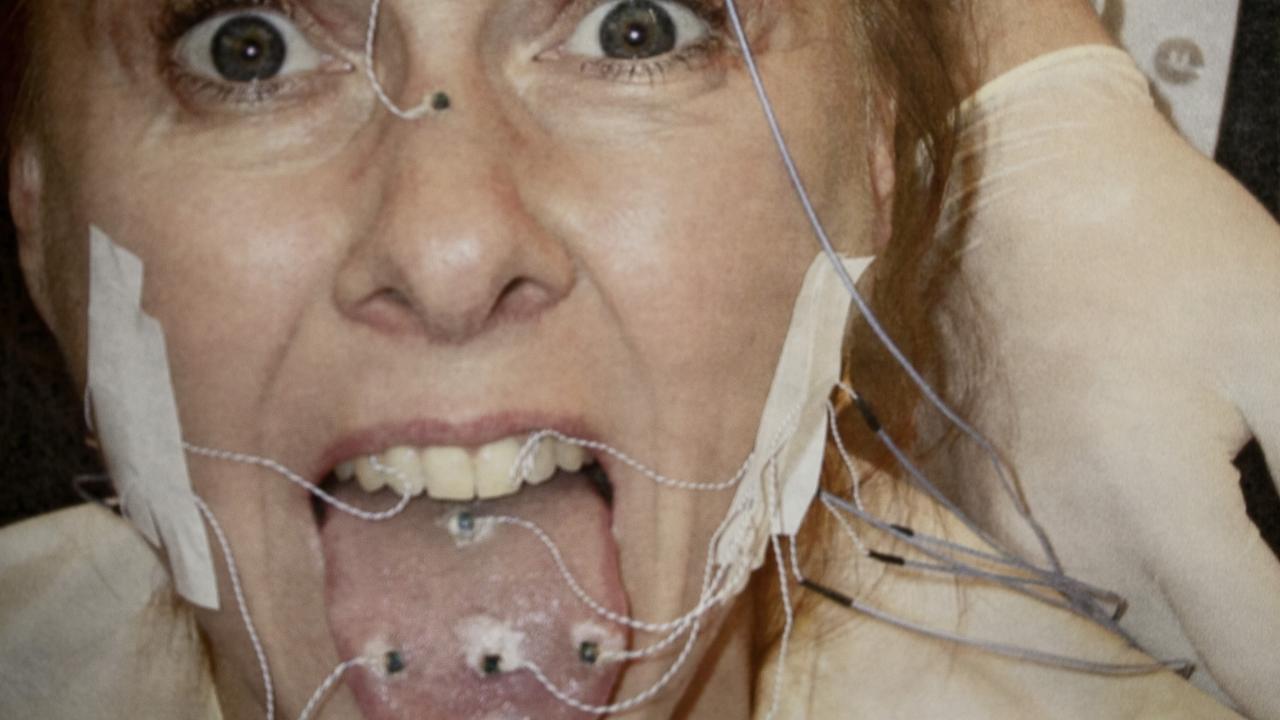

To assist her she has a number of different technical aids at Lund University Humanities Lab, including an articulograph that measures tongue movements, motion capture that measures bigger body movements such as gestures, and equipment to measure brain activity.

– We’ll also be recording for example French and Swedish people speaking each other’s languages to see what irritates a native speaker the most – deviations in speech, gestures, or both

After ten years as a research leader at the Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics in the Netherlands she was appointed Scientific Director of Lund University Humanities Lab in 2010.

– It was an offer I simply couldn’t refuse. There is nothing like the Humanities lab anywhere in the world. We host researchers from all disciplines except Law.

Her research team is of many different nationalities and she herself speaks seven languages fluently. Despite her coming from a monolingual home where the only language variation was that between the Halland and Skåne dialects. Nor has it always been a matter of course that she would become a researcher.

– I have worked both as a journalist and a translator. I was about to start training in simultaneous interpretation before opting for research, she says. I have never regretted my choice.

Text Ann Fernholm

Translation Semantix

Photo Magnus Bergström